Additional Participating Entity:

Federal Aviation Administration / Flight Standards District Office; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Investigation Docket - National Transportation Safety Board:

Location: Cape May, New Jersey

Accident Number: ERA19FA184

Date & Time: May 29, 2019, 11:15 Local

Registration: N201DG

Aircraft: Mooney M20J

Aircraft Damage: Substantial

Defining Event: Miscellaneous/other

Injuries: 1 Fatal

Flight Conducted Under: Part 91: General aviation - Personal

Analysis

The pilot was seen by multiple witnesses flying low just above the ocean surface near the shoreline. One witness stated that he saw the airplane flying about 10 ft above the ocean when it contacted the water, climbed about 100 to 200 ft, then entered a steep dive and impacted the water in a near-vertical attitude.

Postaccident examination of the wreckage revealed no pre-impact mechanical deficiencies that would have precluded normal operation of the airplane. Following a death investigation, the state medical examiner classified the manner of death as suicide.

Probable Cause and Findings

The National Transportation Safety Board determines the probable cause(s) of this accident to be:

The pilot's intentional flight into water as an act of suicide.

Findings

Personnel issues Suicide - Pilot

Factual Information

History of Flight

Maneuvering-low-alt flying Miscellaneous/other (Defining event)

On May 29, 2019, at 1115 eastern daylight time, a Mooney M20J, N201DG, was destroyed when it was involved in an accident near Cape May, New Jersey. The commercial pilot was fatally injured. The airplane was operated as a Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 personal flight.

In a written statement, a witness described seeing the airplane flying parallel to the beach about 10 ft above the water. He stated that it appeared "stable and in control but then dipped, hit the water, and skipped up out of control." The airplane entered a steep climb to around 100 to 200 ft above the water, “stalled, turned downward, and plunged almost straight into the water." The witness estimated the pitchup attitude of the airplane after it contacted the water at 65° to 70° and its nose-down attitude at 75° to 80° during the descent.

A Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) aviation safety inspector stated that reports of a low-flying airplane travelling along the beach from north to south were received from several towns north of Cape May. Witnesses reported that the airplane would dive to the surface, fly low along the beach, and climb again.

One witness forwarded a video of the airplane as it passed her position on Diamond Beach, about 5 miles, or about 2.5 minutes, north of the accident site. The airplane was near the shoreline, about 10 ft above the wave break, and the sound of the engine was smooth and continuous throughout. At one point, the airplane descended below the horizon line. About 20 seconds into the 30-second video, the airplane began a steep climb. The airplane was about 200 ft above the surface when the video ended.

State and local law enforcement attempted recovery of the pilot in the days following the accident but were hampered by the strong current, low visibility, and storms. On June 1, 2019, a commercial underwater salvage operator recovered the pilot along with the wreckage.

Pilot Information

Certificate: Commercial

Age: 58,Male

Airplane Rating(s): Single-engine land

Seat Occupied: Left

Other Aircraft Rating(s): None

Restraint Used: Unknown

Instrument Rating(s): None

Second Pilot Present: No

Instructor Rating(s): None

Toxicology Performed: No

Medical Certification: BasicMed Without waivers/limitations

Last FAA Medical Exam: September 20, 2018

Occupational Pilot: No

Last Flight Review or Equivalent:

Flight Time: 333 hours (Total, all aircraft), 17 hours (Total, this make and model), 6 hours (Last 30 days, all aircraft)

The owner/operator of the airplane stated that the pilot had "returned" to flying in October 2018. Training and rental records revealed that, since that time, the pilot had completed online FAA flight review training, received 17 hours of dual instruction, and had accrued 44.1 total hours of flight experience.

Aircraft and Owner/Operator Information

Aircraft Make: Mooney

Registration: N201DG

Model/Series: M20J No Series

Aircraft Category: Airplane

Year of Manufacture: 1977

Amateur Built: No

Airworthiness Certificate: Normal

Serial Number: 24-0110

Landing Gear Type: Retractable - Tricycle

Seats: 4

Date/Type of Last Inspection: February 13, 2019 Annual

Certified Max Gross Wt.: 2899 lbs

Time Since Last Inspection:

Engines: 1 Reciprocating

Airframe Total Time: 5233.2 Hrs as of last inspection

Engine Manufacturer: Lycoming

ELT: Installed, not activated

Engine Model/Series: IO360-A3B6D

Registered Owner:

Rated Power: 200 Horsepower

Operator: On file

Operating Certificate(s) Held: Pilot school (141)

Meteorological Information and Flight Plan

Conditions at Accident Site: Visual (VMC)

Condition of Light: Day

Observation Facility, Elevation: KWWD,23 ft msl

Distance from Accident Site: 5 Nautical Miles

Observation Time: 10:56 Local

Direction from Accident Site: 18°

Lowest Cloud Condition: Clear

Visibility 10 miles

Lowest Ceiling: None

Visibility (RVR):

Wind Speed/Gusts: 7 knots /

Turbulence Type Forecast/Actual: /

Wind Direction: 260°

Turbulence Severity Forecast/Actual: /

Altimeter Setting: 29.75 inches Hg

Temperature/Dew Point: 30°C / 20°C

Precipitation and Obscuration: No Obscuration; No Precipitation

Departure Point: Robbinsville, NJ (N87)

Type of Flight Plan Filed: None

Destination: Robbinsville, NJ (N87)

Type of Clearance: None

Departure Time:

Type of Airspace: Class G

Wreckage and Impact Information

Crew Injuries: 1 Fatal

Aircraft Damage: Substantial

Passenger Injuries:

Aircraft Fire: None

Ground Injuries: N/A

Aircraft Explosion: None

Total Injuries: 1 Fatal

Latitude, Longitude: 38.925556,-74.943054(est)

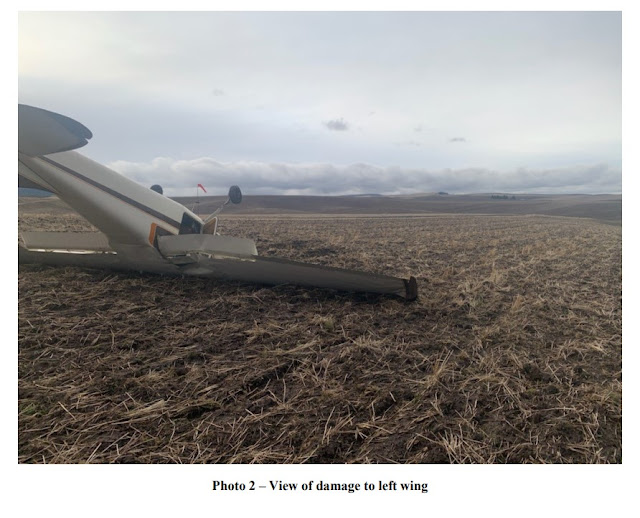

All major components of the airplane were recovered except for the left wing. The roof, left wing, and empennage were separated from the fuselage. The fracture surfaces displayed features consistent withoverload failure. Flight control continuity was confirmed from the cockpit area, through several breaks, to all available flight control surfaces. The fracture surfaces at the breaks displayed features consistent with overstress. The leading edge of the right wing was uniformly crushed aft along its entire span.

The engine was rotated by hand at the propeller and powertrain continuity was confirmed to the accessory section. Thumb compression was confirmed on all cylinders. Examination of the top spark plugs from each of the 4 cylinders revealed signatures consistent with normal wear and saltwater immersion. The single-drive dual magneto was destroyed by impact and saltwater immersion. The engine-driven fuel pump was removed, and when actuated by hand, pumped fluid from the output port. The fuel supply line was removed at the inlet port to the fuel manifold, where trace amounts of fuel were detected.

The propeller was attached at the hub, and all 3 blades displayed similar aft bending.

Medical and Pathological Information

The Office of the Chief State Medical Examiner, Woodbine, New Jersey, performed an autopsy on the pilot. The cause of death was listed as "blunt trauma of head, neck, trunk, and extremities," and the manner of death as "suicide."

The FAA Forensic Sciences Laboratory performed toxicological testing on the pilot. Ethanol was detected in concentrations and distribution consistent with postmortem production. No tested-for drugs were identified.